Giving the players the ability to declare fictional facts is not the same as granting that these fictional facts are indeed true, that decision is still in the GM’s hand. It’s one of the three core roles that the GM has, along with pacing and reacting.

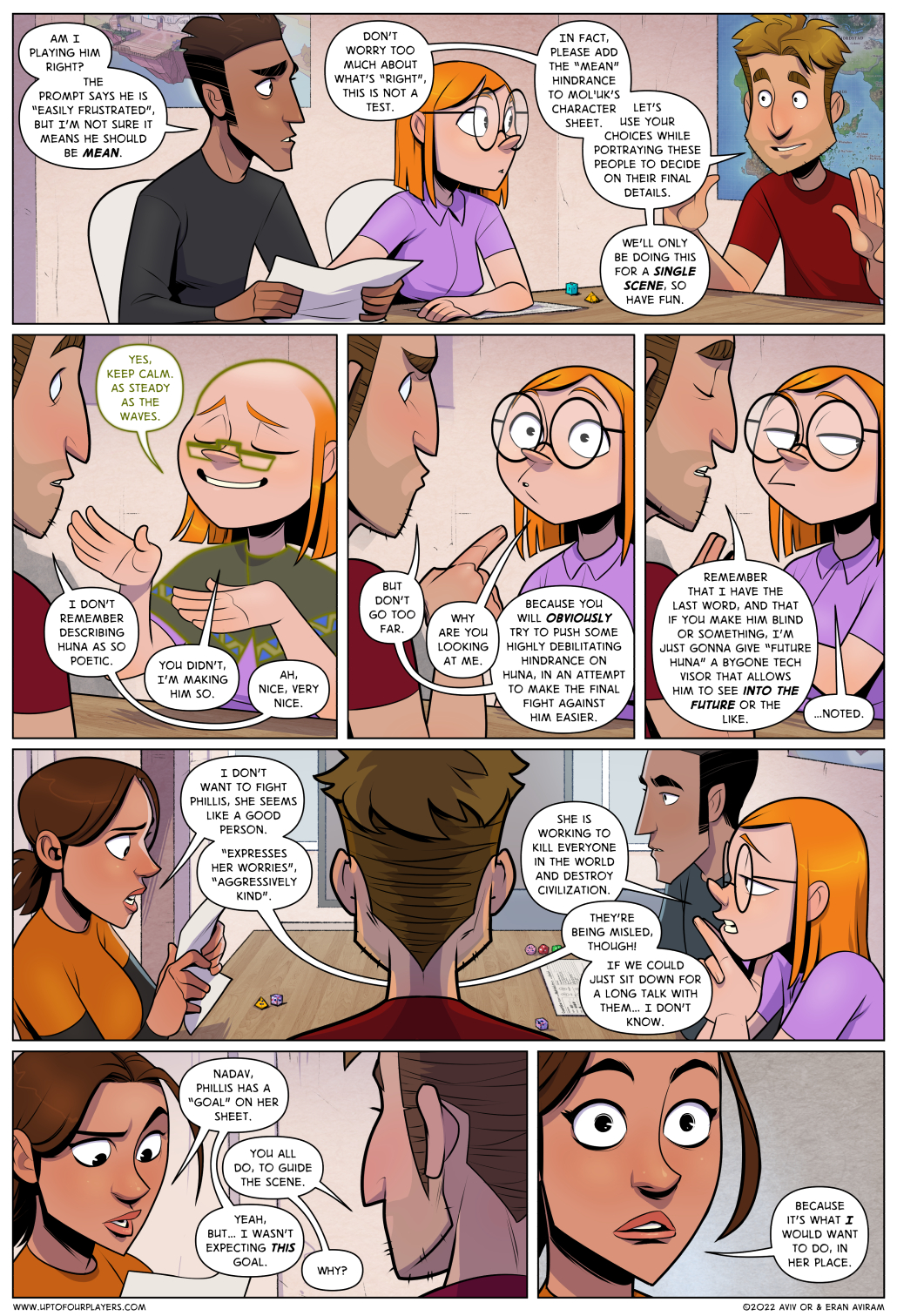

In the case of this page things are a bit different, however. The GM wants the players to feel they can roleplay freely with these guys (so that they get to know them, that’s the whole point), and it would be jarring and counterproductive to stop every two sentences and say “no, Huna doesn’t have a limp” or whatever. So instead, Nadav is granting approval by default. If Lily says Huna has a limp, then Huna has a limp. But not all is allowed, of course. To keep his control, Nadav uses other limiting factors.

The first is the character sheets, which already determine several facts through mechanics, but they also have prompts on them to describe what each character cares about. These guidelines are core to this scene, not optional – if a player behaves contrary to them, Nadav will say “no, this is not what Huna would do”, and it’s not a matter of GM fiat because Nadav can point at the written line that says how Huna would behave. This is very important for maintaining trust, the players must feel there’s a justification for the GM’s ruling.

The second point of control is said by Nadav in panel 4. Because all of this is happening in the past, and because these people are head of the most advanced organisation in the world, and because they weren’t fully “on camera” as their present selves, Nadav has full justification to present their present selves however he wants. Even if one of them is killed, they can be brought back as some cyber-Crystal entity. There’s nothing the players can do to “outsmart” the GM, and it’s important to establish this in order to avoid them even trying – this scene has a goal, and a player who is focusing on “how can I outsmart my GM” will completely miss the intended goal.