First impressions are everything, because they set the expectations to whatever comes next and establish a benchmark against which the rest of the scene is compared.

There are more than enough “how to establish a scene” guides out there, so instead of giving general guidelines like I usually do, I’ll instead just tell you how it looks like in my games.

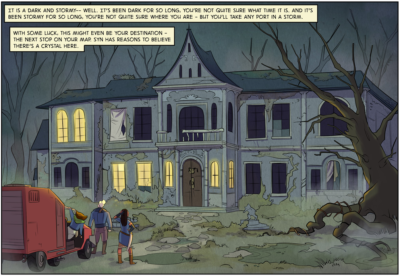

I actually consider the ENTIRE page as part of “setting the scene”, but it’ll be weird to just re-post the whole thing here.

Theme Trumps All

I consider the atmosphere as the most important thing to establish when setting a scene. By ‘atmosphere’ I mean things like theme, genre, high concept, attitude, and so forth. This is why I usually begin with a short and evocative description of the weather and time of day – these two simple things tend to be the backdrop to everything we do, after all, and the way they’re coloured tend to colour everything we do against them. They also help in grounding the story, making it feel more real.

I continue with giving a narrator-like description of the emotional state the character probably feel, the surface thoughts that might be running through their heads. Nothing too big (it’s your character, I won’t tell you how to play it), but just enough to seem reasonable and to leave some things unanswered. I tend to give a few general impressions that everyone gets, then move on to tailor one or two thoughts for every character.

For example: In this week’s page, I begin by giving a sense of confusion, of getting lost (What time of the day is it? Not sure), and “only port in a storm”. It’s quite clear that this manor, and not the swamp around it, is the adventure. I also say “where the local villagers dare not tread”, indicating danger, and “who even lives here?” implying the answer to this question has some importance in what’s to come. At this point the players are already well-aware that this is going to be a mystery story, in a manor, with a dangerous vibe. Now I can build on these expectations, or subvert them – the important thing is, that they’re established.

Occasionally, though, I instead focus on the medium – HOW the information is given, rather than the information itself. This is especially true if the exact time and place are supposed to be fuzzy.

For example: We recently began playing Xcrawl, a cool modern-fantasy setting in which dungeon crawling has become a popular extreme (blood) sport, in the North American Empire. To keep the focus on this absurdity, and to throw us right into the action, I begin each session with “Welcome back from the commercial break!” and immediately go into full commentator mode, talking to “the audience at home”, then handing the microphone to the players, asking each of them to give a short recap of the last session in the form of “highlights”. Then I give a description of the here and now – exactly what’s in front of them (usually the entrance to the next dungeon room), remind them of the crowd shouting in the background, and that’s about it. Go! Anything else could, and should be asked during the game, not as part of the exposition. It’s all a test of your dungeoneering skills, after all!

Intermingle Big Things with Small Details

I tell of the large manor, then say one of the broken windows is covered with a sheet. I tell of the musty smell and bubbling sounds of the swamp mud, then mention a growl from the bushes. Whenever I present something big and noteworthy – such as a manor, the swamp, this butler person, whatever – I also mention one or two specific details about it. This helps establish the fact that everything has more details to it, and also, that I haven’t mentioned them all. So if you want to know more, go ahead and ask, or maybe roll for it.

This approach makes sure the players are aware of the existence of details, without falling to the common meta-game fallacy of assuming every detail I mention is important. In roleplaying games, The Law of Conservation of Details should be a tool, not an assumption. If I mention three doors, “and one of them is red”, it’s quite clear which one the players will check first. If I mention three doors, one red, one slightly open and one with scratch marks on it, these details help establish that there’s no door that’s most important by the mere fact it has details. The players can now explore further.

Get Them Rolling

Place the players at a point where they are either expected to do something (engage in conversation with the butler and enter the manor), or where they have several obvious leads to go with; Unless you don’t want to push for a specific story (let’s say you’re playing a pure sandbox game), and then just leave them at that.

I could have started the scene with “you arrive in front of the manor, what do you do?” but by that I imply there’s something to do. In this case, there really isn’t. All of the adventure is inside the manor, so let’s get to that, and just place the characters in front of the door, engaged with the butler.

There will, of course, be occasions where one player is gonna jump and say “Wait! I want to use my detect super-evil presence before entering”, but that can easily be handled as “Sure, roll for it, you did that just before you guys approached the door.” This declaration, of course, shouldn’t be used as a ‘trap’ – if there is something super-evil to detect, and that thing is likely to make the players reconsider whether to enter the manor from the front, you shouldn’t place them already at the door. By placing them there, you signal to them “guys, trust me on this, there’s nothing interesting for you to do outside, and I wouldn’t push you into a trap.” Keep doing that, build trust, and you’ll have the best game.*

*Except for mine; mine is the best.